December 2023

Tips for Writers:

The Cost of Self-Publishing

by

Ray ‘Rusty’ Strait

Click above to see video

A friend (not a writer) recently asked me how much it costs to self-publish a book, understanding that I had self-published my last book. There are so many aspects of the question that I’m not sure where to start, but I’ll try to expand my brain enough to answer.

The following all contribute to price:

1. The number of pages in your book,

2. Even if you have conceived a cover, it will still cost to do all the art work involved.

3. Do you have photos? How many? Are they in black and white or color? On interior photo in color means the entire book is in color.

4. Publicity. You are the publisher, so the cost of publicity is your responsibility.

5. Finding book reviewers. Newspapers and magazines are the best source. They usually have someone that reviews books. However, some agencies charge various fees. They usually give a decent review, but lack standing in the publishing world. Kirkus is the Godfather of reviews, but even they charge.

6. A service that does line editing to make sure your P’s & Q’s are in place

One additional fact a writer needs to consider—editing for plagiarism and other liabilities. Accuracy is key to non-fiction. In fiction, if you have real settings and characters buried in your story, you need to be careful of liable. Nowadays, people love to sue for damages - like money.

These are just some of the basics that you will encounter if you self-publish. As you go along, you will find that prices vary depending on who you use for things you nothing about. In this instance the early bird gets stuck with the bill. Better to talk to your librarian if you have no other source of such information.

However if you love writing and can afford the costs of self-publishing, go for it. It is a lot of fun, and the things you discover along the way are awesome.

Thanks for listening and I do appreciate your interest and inquiries. Writing is my life.

Just sayin’

Ray ‘Rusty’ Strait was Jayne Mansfield’s private secretary for close to ten years. He is the author of over thirty books, most of which are biographies of celebrities. His latest book, Bug House Blues is a coming-of-age novel set in Chicago in the early 1940s.

September 2023

Tips for Writers:

THE BENEFITS OF VULNERABILTIY

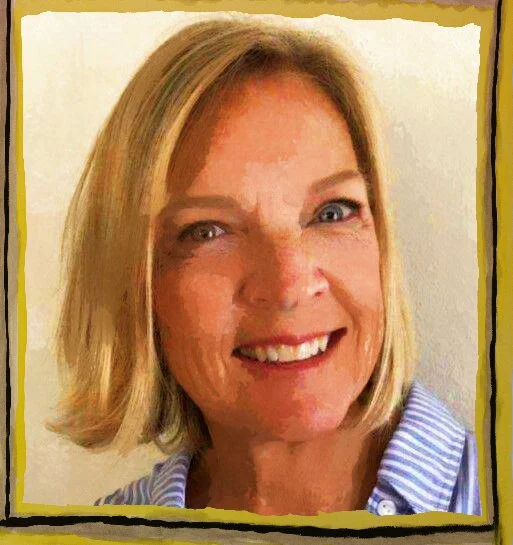

Ellyn Wolfe

To say I was anxious about publishing my memoir is a gross understatement. I had laid bare my deepest self, which left me feeling nervous and vulnerable.

After six years of writing and rewriting Grateful for the Color Blue: Surviving the Loss of an Adult Child, I let another year pass then recalled my mantra while writing, “If this book helps even one person, my vulnerability will be worth it.” I loaded the manuscript into Amazon KDP, held my breath, and pushed the PUBLISH button.

Immediately, the reader reviews and thank you emails let me know my book was hitting its mark. They found comfort, related to my wild emotions, and laughed out loud at my humor. I released the breath I had been holding since I let Grateful for the Color Blue go public. My vulnerabilities turned to relief.

Then a surprise came in an email from Jeff, a friend fifty-plus years in my past. “We knew each other in Glen Ellyn,” it read. “In 1963, you and Penny cruised past my teenage house in her parent’s red Buick convertible a few times when she had a temporary infatuation with me.”

I remembered, but it was only a two-second flash—riding past a white house with light blue trim, low green bushes along an empty driveway, Penny excited, hoping Jeff would step out of his house as we crept past … three times.

I read on. “In the spring of 1964, I picked you up on a mild and sunny afternoon. I was in possession of two pairs of red, wooden Dutch shoes which we each donned to go clomping through Lilacia Park in Lombard. The lilacs were in full bloom and smelled like heaven.”

Really? Red wooden clogs? I don’t remember. But wait. I remembered Lilacia Park with its hundreds of purple and white lilac bushes in full bloom. I remembered the evocative scent. And I had a flash of those shoes on the floor of a car, my feet next to them. Maybe, just maybe, I had a dusty hint of trying to walk in those red wooden shoes and laughing.

But was it real? Or was his suggestion so alluring my mind was manufacturing a memory because I wanted to be in Lilacia Park in red Dutch clogs? I wish I had the gift of a detailed memory, or access to Dumbledore’s Pensive from the Harry Potter books. The wizard put a wand to his head, pulled out a memory, placed it in the Pensive’s water, and the whole scene, complete with audio, magically appeared.

If only.

The flashback stories I wrote about my family triggered Jeff’s memories— “I had amicable dealings with your dad on three occasions,” he wrote.

Jeff must have had car-related issues. My dad was an autobody repair guy. I wanted to hear his stories as Dad’s been gone for over thirty years. But that’s all Jeff wrote about him.

“Your references to ‘greasers and socialites’ brought back memories. In my case, my protective sister was the socialite. While I may not have been the full-blown greaser that your brother was, I was certainly a wannabe greaser.”

I laughed out loud.

Then Jeff got to the heart of his email.

“This is about my brother, Craig. I read your book. On August 15, 1970, I got a call from a former Glen Ellyn neighbor who informed me that my brother, Craig, just shy of his twenty-fifth birthday, had drowned in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. I was shocked. I hadn’t realized how much I loved him.

“Time eventually masked our family's outward sorrows, but my mother was never the same. After Craig died, I softened. I became aware that I had become much more empathetic toward the parents and kin of young people who died prematurely. That is the nerve your book touched.”

Oh. Craig. I’m stopped in my tracks because I remember clearly my shock when I heard about his death.

Traumatic events and the strong emotions that go with them are stored differently in the brain than everyday memories and are easily triggered at any time. Craig’s death was traumatic, and this is why I remember it so well, and why I’m vague about the red wooden shoes.

“Your email pulled me right back into the fun memories of Glen Ellyn and the Sixties,” I wrote in reply. “Thanks for helping me retrieve at least a little bit of that crazy day in Lilacia Park.

“I remember your brother, Craig, well. He took me flying—my first time in a small plane. He was smart and wanted to be an astronaut. I remember my shock when I heard he died. I'm so sorry you lost your brother. When you said, ‘I wonder what his future would have been,’ I get it. I often wonder the same about my son.

“And I understand about your mother and how the grief never fully goes away. I love that you read my book and that you contacted me. You’re from my past, but now you’re part of my present.”

I also asked him about his dealings with my dad. Jeff wrote back and told me how my dad fixed the tail pipe on his mom’s car with a secret switch under the dashboard that, when flipped, allowed him to rumble through town sounding like a cool hot rod greaser, then switch it back to a mild suburban car once home. “I think your dad knew it wasn’t my car, and that I didn’t have permission to do what I asked him to do. His sly smile gave him away.”

I love this story! That sly smile, indicating of course he knew, yet was willing to take part in this young teen’s fantasy. That’s my dad. This story is a gift to me from Jeff, and only happened because I allowed my vulnerability to go public when I published Grateful for the Color Blue.

I wrote back, told him how much I loved the story about my dad, and told him more about my dates with his brother.

When Jeff replied, “I wasn’t aware you knew Craig, nor did I know he wanted to become an astronaut,” I knew then his gift to me, the story about my dad, had been returned to him in kind.

Digging deep to write about painful memories had been frightening for me. But with each thank you that came my way, with each story from readers like Jeff, I learned that vulnerability has its benefits.

August 2023

Writing Tips from author

Lynne Spreen

July 2023

LIES OUR WRITING TEACHERS TOLD US:

#2--SHOW. DON’T TELL

Ordinarily, ‘SHOW. DON’T TELL’ is good advice, especially when an author uses active rather than passive verbs. If you are writing fiction or narrative non-fiction, active verbs—showing—moves the story along at a faster clip. We see the events as if they are all part of a movie. If you look at the later works of Robert Parker, he kept his narratives rolling along at a fast pace and seldom if ever indulged in backstory. He relied on dialogue and straight-forward, active sentences.

At times, however, authors may need to cover a multitude of events or jump forward in time or present a backstory. In such cases, an author can—and in some cases must—resort to telling. Even then, if he or she can cover the material with active verbs, the telling appears to be showing . Here is an example from my latest novel Storm Riders (Five Star, 2022).

The Four-Square Emporium made most of its money from an assorted crowd. While a number of white boys frequented the establishment, especially at night, Mexicans and colored men like Pappy comprised the majority of the clientele. Even during the middle of the day, we kept the interior dark. We seldom cleaned the front windows, heavy with dust. A single kerosene lamp hung from the ceiling, the wick low so the tables along the walls lay in deep shadows, which attracted customers rather than repelled them. In the evenings, when the girls came out—and we hired the best-looking girls in Southern Texas—the darkness concealed the men from their wives and sweethearts.

As you can see, this gives backstory and description in the same passage. Yet, I never once used a ‘was’ or ‘were.’ The active verbs give movement where this is little. ‘Was’ and ‘were’ or any form of these words are not intrinsically bad. Times arise when they are the only alternatives to writing clunky or convoluted sentences. Still, the less an author uses them, the better, even when telling rather than showing.

These days, if you watch golf on TV, you can hear the miked-up player and his caddie discussing every aspect of the upcoming shot in excruciating detail. It makes my head hurt to think of all they know, but that’s what happens when you’re a pro. You learn a lot. Or you should.

Similarly, a professional author (one who writes every day, publishes regularly, and sells her works) gains knowledge as she writes. There’s so much to know. Character development and plot twists, grammar, structure, pacing, rules about what to do and what to avoid (and when to break those rules–or not), and then there’s editing, cover design, publicity, marketing…it’s a lot. The good news is, continuous learning is supposed to help your brain stay young and healthy.

After nine novels (and counting), I’ve learned a few strategies for writing fiction. Here are some of my favorites.

Embrace lying. After a fact-dependent career in corporate America, I found that making stuff up out of thin air was fun and freeing, and it's better for your writing, because...

Invent characters who aren’t like you. Revel in the creation of characters who do awful or amazing things you would never.

Along those lines, check out the character-idea books by Angela Ackerman and Bella Puglisi. They are goldmines! The Emotional Wound, Positive Traits, Negative Traits, and Conflict thesauruses are especially helpful.

Your story should have a point. Why are you writing this book? What’s in it for the reader? Bonus: knowing the point will drag you out of the doldrums if your enthusiasm flags.

To increase output, dictate into your phone. Google Docs are good for this. Bonus points if done while walking, which helps combat writer’s spread.

Give your character an exceptional skill, even if it's organizing sock drawers or baking cookies. Bonus points if that skill plays a part in your fabulous ending.

Along those lines, do you ever wonder how to end a story? Best advice I ever got: have the end mirror the beginning. Examples: in the beginning, the hero freezes when speaking to her library group…at the end, now a total badass, she wows a crowd on a concert stage. In the beginning, the hero is a callous jerk…in the end, he performs an act of heartbreaking sacrifice.

When you think your manuscript is ready to send to the editor, read it out loud to yourself first–the entire thing. Pretend you’re speaking into the ear of your audiobook reader. Believe me, this will save you a lot of embarrassment later.

I hope these tips have been helpful. Now, get busy. Your book isn’t going to write itself.

June 2023

LIES OUR WRITING TEACHERS TOLD US:

#1--WRITE WHAT YOU KNOW

I believe it was Mark Twain who told us to write what we know. For him, it worked out well. He lived Roughing It and Life on the Mississippi. He set The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in and around Hannibal, Missouri, where he lived, and on the Mississippi River.

But I would like to point out that he violated his own advice in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, which he published in 1889. While he did his research for the book, he stepped outside himself and created a fantasy world set in the Middle Ages. I regard this as his most enjoyable, fully-realized novel for adults.

When a person sets out to write a non-fiction book, Mark Twain’s advice holds far more weight. In my own case, I was a film buff, especially of Westerns. I also loved Western fiction and held a MA in History and English. The first articles I sold to magazines involved real life Western cowboys, outlaws, and native Americans who made movies during the silent era. This led to my first book contract, The American West: From Fiction Into Film (Mcfarland, 1990), which Publisher Weekly called ‘the definitive monograph on the subject.’ My second book, Words and Shadows (Citadel, 1992), explored mainstream American literature made into films.

However, when I turned to writing fiction, my first published novel was Carny, a Novel in Stories (Aberdeen Press, 2010). What did I know about a carny? Not much. My father’s second and third wife—her name was Becky—worked the carny circuit. I was a child at the time. I heard a few stories, but that was it. I started with a single story of a hunchback who approaches the carny boss and asks for a gift for his birthday. From there, the book took shape. I found a half dozen books on carny life, did my research, and from that, emerged a book that won the Grand Prize for Fiction in the Next Generation Indie book Award.

The Courage of Others (Open Books, 2015), which was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, followed. The story is told from the POV of teenage boy in 1919 Texas. Racism is at the center of the story. I grew up in Texas in the 1940s and 50s, so I was familiar with the social framework . But what did I know of 1919? Of veterans returning from WW I? Of racism from an African-American’s point of view? Yet, one reviewer said this book should be taught in every high school in America.

My two latest novels, Bodie (Black Horse Press, 2019) and Storm Riders (Gale Publishing, 2022), are Westerns. Though I have visited the ghost town of Bodie and, for Storm Riders, traveled the Llano Estacado, I possess no first-hand knowledge of life in the 1870s and 1880s. I had to do a great deal of research for both books, and both have received excellent reviews.

In Storm Riders, I made the decision to make my narrator an African-American of mixed parentage. I had to step out of myself to create a character of flesh and blood. He became my favorite character in the book.

As for Mark Twain’s advice, it is fine some of the time.

But it should never be taken as an absolute.

Authors should never be afraid to step out of themselves—

—Or to boldly go where they’ve never gone before.

MAY 2023

HITT’S GOLDEN RULES OF STYLE AND GRAMMAR

(These rules apply equally to fiction and non-fiction)

1. Remember the HITT #1 GOLDEN RULE OF WRITING:

Brevity and clarity equal good writing.

Brevity means to say as much as you possibly can in the fewest amount of words;

Clarity means to go directly to the point. Say what you mean!

2. Remember that the most important word in any sentence is the verb. Make sure you have chosen the strongest possible verb for your sentence.

3. Whenever possible, use active verbs rather than passive verbs. Especially avoid is. ar a was. were

4. Avoid all use of be been being (to be is an exception).

5. Avoid the use of no not orany contraction using n’t.

6. Avoid all use of such words as:

always seems you got alot guy really very just

(Note: Remember that this means any form of these words,

i.e. Your or you, seems or seemingly, etc.)

7. Avoid whenever possible the uses of adverbs, especially those that end in ly. You can do this by choosing strong verbs and strong adjectives.

8. All these rules are null and void in dialogue.

April 2023

GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS

My first successes came in the early1980’s when I was a full time English teacher at Royal High in Simi Valley, California. I wrote articles for Real West and True West. Other magazine publications followed, but these two launched my writing career. Many of my articles dealt with real outlaws and cowboys and the films made about them, such as Emmitt Dalton and Al Jennings who, after their release from prison, made movies.

These articles generated a degree of interest to the point that one day in late 1984, the editor of True West offered me an assignment—the western films of President Ronald Reagan.

The President-elect made many films but only six westerns. In my finished article, I discussed the plot of each film, the critical reception each received, and Reagan’s view of each film. The conclusion told of Reagan’s love of the West and his love of making western movies. I never touched on politics. The article was about his western films. Nothing more.

A month after the article appeared—and my story was the lead article—the editor called me at home. “Jim,” he said, “I have some good news and some bad news. The good news is that we had more response from your article than any piece we have ever published.”

“That’s great,” said I.

“We have also had more cancellation of subscriptions.”

After that, they never again published articles dealing with film.

Good news, bad news.

Raise you up, bring you down.

That’s the thing about being a writer. You have the ups and the down. For most of us, less ups, more downs.

Only one writer I ever heard about who never received a rejection—Amy Tan, but most of us could wallpaper a whole house with rejection slips—or e-mail rejections in today’s market.

Why do writers write?

We write because we write.

We write because we must.

We write to be read.

So you’ve written a novel.

In that case, I’ve some good news and some bad news.

Which would you like first?